|

|

|

|

| Visite: 7578 | Gradito: |

Leggi anche appunti:Il concetto di alienazione in campo socio-umanisticoIl concetto di alienazione in campo socio-umanistico L'alienazione Cime Tempestose analisi sequenze e temiCime Tempestose analisi sequenze e temi Macrosequenze narrative: S Cap Sulla tomba del fratelloSulla tomba del fratello Introduzione Nel viaggio di ritorno |

|

|

Oltre all'idealismo filosofico, il movimento romantico conoscerà

un periodo di vasta produzione anche nella musica, nell'arte e nella letteratura.

Ciò che colpisce chi osserva nel suo complesso la cultura romantica, è che in

questo periodo trionfano delle tematiche negative ed irrazionali: il dolore, la

noia, il male, il rifiuto della realtà, l'infelicità, la tensione verso

l'infinito. La tematica della tensione verso l'infinito ricorre in tutta la

letteratura europea ed in particolare in que lla italiana, di cui Giacomo Leopardi è uno dei massimi interpreti.

lla italiana, di cui Giacomo Leopardi è uno dei massimi interpreti.

Al centro della meditazione di Leopardi si pone principalmente un motivo pessimistico: l'infelicità dell'uomo. Egli espone le cause di questa infelicità in alcune pagine dello Zibaldone del luglio 1820. Identifica, infatti, la felicità con il piacere, sensibile e materiale. Ma l'uomo non desidera un piacere ben determinato bensì il piacere: aspira cioè a un piacere infinito per estensione e durata. Purtroppo, siccome nessuno dei piaceri terrestri può soddisfare questa esigenza, nasce in lui

Figura - Giacomo Leopardi

un senso di insoddisfazione perpetua che sfocia nell'infelicità e nel sentimento della nullità di tutte le cose.

"Il sentimento della nullità di tutte le cose, la insufficienza di tutti i piaceri a riempirci l'animo, e la tendenza verso un infinito che non comprendiamo, forse proviene da una cagione semplicissima, e più materiale che spirituale[1]. L' anima umana desidera sempre essenzialmente, e mira unicamente, benché sotto mille aspetti, al piacere, ossia alla felicità, che considerandola bene è tutt'uno col piacere. Questo desiderio e questa tendenza non ha limiti: né per durata, né per estensione.[.] Quando l'anima desidera una cosa piacevole, desidera la soddisfazione del suo desiderio infinito, desidera veramente il piacere, e non un tal piacere; ora nel fatto trovando un piacere particolare, e non astratto, ne segue che il suo desiderio non essendo soddisfatto di gran lunga, il piacere è appena piacere. E perciò tutti i piaceri devono essere misti di dispiacere, come proviamo, perché l'anima nell'ottenerli cerca avidamente quello che non può trovare, cioè un'infinità di piacere, ossia la soddisfazione di un desiderio illimitato" (Zibaldone, 165-167 ).

L'uomo è dunque, per Leopardi, necessariamente infelice. Ma la natura ha voluto sin dalle origini offrire un rimedio all'uomo attraverso l'immaginazione e le illusioni. La realtà immaginata costituisce l'alternativa ad una realtà vissuta che non è che infelicità e noia. Ciò che stimola l'immaginazione a costruire questa realtà parallela, in cui l'uomo trova l'illusorio appagamento al suo bisogno di piacere infinito, è tutto ciò che è vago, lontano, indefinito.

In altri passi dello Zibaldone, Leopardi passa in

rassegna quegli aspetti della realtà sensibile, che per il loro carattere

indefinito, possiedono questa forza suggestiva. Si viene a creare una vera e

propria teoria della visione che ci spiega "come degli oggetti veduti

per metà, o con certi impedimenti, ci destino idee indefinite"(Zibaldone,

1744). È piacevole, quindi, per le idee vaghe che suscita, la vista di un

ostacolo, come una siepe, una torre, una finestra, "perché allora in luogo

della vista, lavora l'immaginazione e il fantastico sottentra al reale"; lo stesso

effetto hanno un filare di alberi che si perde all'orizzonte o una fuga di

stanze. Contemporaneamente viene a costruirsi una  teoria del suono secondo cui "è piacevole per

se stesso, cioè non per altro, se non per un'idea vaga ed indefinita che desta,

un canto (il più spregevole) udito da lungi o che paia lontano senza esserlo, o

che si vada appoco appoco allontanando, e divenendo insensibile o anche

viceversa (ma meno) o che sia così lontano, in apparenza o in verità, che

l'orecchio e l'idea quasi lo perda nella vastità degli spazi" (Zibaldone,

1927).

teoria del suono secondo cui "è piacevole per

se stesso, cioè non per altro, se non per un'idea vaga ed indefinita che desta,

un canto (il più spregevole) udito da lungi o che paia lontano senza esserlo, o

che si vada appoco appoco allontanando, e divenendo insensibile o anche

viceversa (ma meno) o che sia così lontano, in apparenza o in verità, che

l'orecchio e l'idea quasi lo perda nella vastità degli spazi" (Zibaldone,

1927).

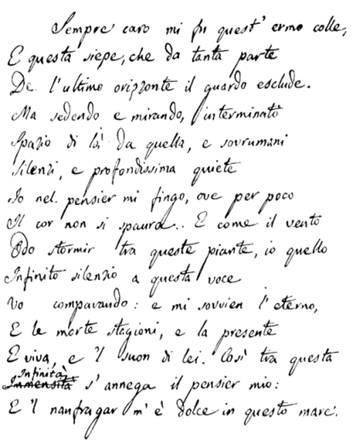

Le teorie filosofiche dell'indefinito e del vago elaborate nelle fitte pagine dello Zibaldone, si riflettono nella produzione poetica di Leopardi, specialmente nell'Infinito.

Figura - Manoscritto dell'Infinito

Composto a Recanati nel 1819, l'idillio offre nella sua perfetta brevità la meditazione più alta e compiuta del tema dell'infinito. L'infinito di cui parla Leopardi è una dimensione spazio temporale non esistente in sé, "è un parto della nostra immaginazione, della nostra piccolezza ad un tempo della nostra superbia [.]l'infinito è un'idea, un sogno, non una realtà. Almeno niuna prova abbiamo noi dell'esistenza di esso, neppur per analogia" (Zibaldone).

La contemplazione dell'infinito si articola in due momenti distinti. Nel primo momento la contemplazione è data da una sensazione visiva o meglio dall'impossibilità della visione: la siepe che chiude lo sguardo.

Ma l'impedimento della vista fa subentrare l'immaginazione del pensiero: il pensiero si costruisce l'idea di un infinito spaziale, senza limiti, immerso in una quiete profonda.

Nel secondo momento l'immaginazione prende l'avvio da una situazione uditiva, lo stormire del vento tra le piante. La voce del vento viene paragonata ai silenzi prima immaginati e richiama così l'idea di un infinito temporale, a cui si associa il pensiero delle epoche passate e svanite, e la realtà presente, destinata anch'essa a svanire. Le due sensazioni e le due immaginazioni da esse suscitate scaturiscono l'una dall'altra; questa successione narrativa non si riferisce però ad un evento unico bensì ad un esperienza ripetuta più volte nel tempo ("Sempre caro mi fu."). Nell'idillio si ritrova anche un passaggio psicologico: l'io, di fronte alle immagini interiori dell'infinito spaziale, prova un senso di sgomento ("per poco il cor non si spaura"), ma nel secondo momento l'io s'"annega" nell'"immensità" dell'infinito (spaziale e temporale) sino a perdere la sua identità ("il naufragar m'è dolce in questo mare").

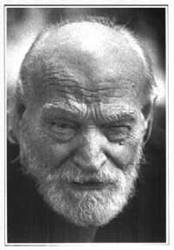

L'idea di infinito ricorre anche nella produzione poetica del primo dopoguerra mondiale trovando alcuni suoi maggiori interpreti in Giuseppe Ungaretti.

Nella sua poesia, Ungaretti mette in evidenza la possibilità di riprodurre il miracolo di una riconciliazione dell'uomo con l'assoluto. Egli, in quanto poeta, si innalza ad un intimo contatto con l'assoluto portando alla luce un ideale universale di verità. Ma l'assoluto cui l'uomo tende è per definizione ineffabile e inesprimibile in quanto trascende la capacità umana di espressione. Il che significa che questo assoluto non può essere compiutamente descritto, ma solo richiamato allusivamente attraverso gli artifici del simbolo, della metafora, dell'analogia.

Figura - Giuseppe Ungaretti

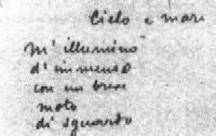

Nella poesia Cielo e mare, tratta dalla raccolta Allegria, il poeta esprime una folgorazione subita che giunge a percepire un sentimento di infinito:

Figura - Manoscritto di Cielo e Mare

Durante una mattina di sole, i soldati in guerra e Ungaretti stesso sono nascosti in una trincea; all'improvviso scorgono la distesa infinita del mare e s'illuminano "d'immenso".

Questa prima versione del testo esplicitava la separazione tra due piani visuali: la luce del cielo e l'immenso del mare. Il titolo Cielo e mare però rappresentava una traduzione quasi naturalistica del contenuto dei versi. Per questo motivo Ungaretti accantonò il titolo originale trasformandolo in:

Mattina

M'illumino d'immenso

Così l'autore elimina l'elemento esteriore e punta esclusivamente sulla concentrazione interiore: l'immensità è il luogo dello spirito in cui si acquietano tutti i desideri di infinito e di eterno dell'uomo. L'analogia pone quindi in stretta relazione il finito, rappresentato dalla piccolezza dell'uomo, e l'infinito, rappresentato dall'immensità dell'assoluto in cui cielo, terra e mare si fondono. Così anche il pronome Mi richiama l'individualità del poeta, che attraverso la vista della luce, passa ad una vera e propria comunione con l'assoluto, creando una condizione non dissimile da quella cantata nell'Infinito leopardiano.

By the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th (Romantic period), the new sensibility, linked to the importance of nature, imagination and irrationality, became dominant and began to influence numerous poets and philosophers.

This is due to the fact that modern society was characterized by a productive and organized rationality which limited artists' imagination. Reason also seemed powerless to correct the evils of industrialized society such as misery, ugliness and nature contamination. So Romanticism is especially an exploration of irrationality revealed in obscure and mysterious metaphors. To escape from the mental prison of reason, artists find a refuge in altered psyche states: madness, drunkenness, hallucinations and dreams. However some poets considered these ways of transcending reality weren't enough. For them, the most vital and precious possession of the mind was imagination: thanks to imagination the poet could discover a supernatural order and see things to which the ordinary intelligence is blind. For example the thought about the absolute, the infinity was a big aspiration for the poet; an aspiration he didn't have the possibility to reach. The aim to approach the boundlessness and the endlessness brought poets to deal with remote times and places. Childhood is seen as a lost paradise of innocence and joy in which dreams and imagination hide the hideous reality.

In addition to imagination and

memory, nature becomes another source of inspiration regarded as a "living

force" and as the expression of immensity of the universe. The poet acquires

the role of a "visionary prophet" whose task is to mediate between men and

nature and give voice to the ideals of beauty, truth and freedom.

In addition to imagination and

memory, nature becomes another source of inspiration regarded as a "living

force" and as the expression of immensity of the universe. The poet acquires

the role of a "visionary prophet" whose task is to mediate between men and

nature and give voice to the ideals of beauty, truth and freedom.

Among the English romantic poets, the one who best represents the atmosphere of infinite and supernatural mystery is Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834). Unlike Wordsworth, who represented ordinary things with the aim of interesting the reader, Coleridge used to concentrate his compositions on visionary and supernatural topics.

Figura - Samuel Taylor Coleridge

For Coleridge poetry was no longer an imitation of life but coincided with the desire to challenge the cosmos and nature. Even on this point the difference with Wordsworth is essential: Coleridge did not view nature as a guide or source of happiness. He rather perceived nature as an imperfect reflection of the perfect world of "Ideas". Thus he believed that natural images carried abstract meanings and used them in most of his poems.

As the other romantic poets, Coleridge considered imagination as the most important ability of the poet. In his Biografia Literaria, he distinguishes between "primary" and "secondary" imagination:

"Primary" imagination is a synthesis of human physical perception of the world and ability to create images and thoughts about it.

"Secondary" imagination is something more: "it dissolves, diffuses in order to recreate". It's the real poetic faculty which gives order to our world and additionally creates other worlds.

We can find these two types of imagination in Coleridge masterpiece, The Rime of the ancient Mariner written in 1798. The atmosphere of the whole poem is charged with mystery because of the combination of the supernatural and the commonplace, reproducing the impossibility to penetrate the unknown and the infinity.

The tale begins with the Mariner's ship leaving harbour; despite initial good fortune, the ship is driven off course by a storm and, driven south, eventually reaches Antarctica. An albatross, traditionally a good sign, appears and leads them out of the threatening land of ice. Even if the albatross is praised by the ship's crew, the Mariner shoots it with a crossbow, for unknown reasons:

[.] with my cross-bow

I shot the albatross. (81-82).

Figura - With my cross-bow I shot the albatross (Gustave Doré, 1876)

The other sailors are angry with the Mariner, as they think the albatross brought the South Wind that led them out of the Antarctic:

Ah, wretch, said they

the bird to slay

that made the breeze to blow

Nevertheless, the sailors change their minds when the weather becomes warmer and the mist disappears:

'Twas right, said they, such birds to slay

that bring the fog and mist.

The crime arouses the wrath of supernatural spirits who then pursue the ship 'from the land of mist and snow'; the south wind which had initially led them from the land of ice now sends the ship into unknown waters, where it is becalmed.

Day after day, day after day,

We stuck, nor breath nor motion;

As idle as a painted ship

Upon a painted ocean.

Water, water, everywhere,

And all the boards did shrink;

Water, water, everywhere,

Nor any drop to drink.

The surrounding infinity of water overwhelms the mariners with fear and desperation. The sea is perceived as a place, at same time, sublime and painful: man cannot stand the ravaging power of nature. The same theme of the see as an abyssal place will be developed by romantic painters such as Caspar David Friedrich.

Here, however, the sailors change their minds again and blame the Mariner for the torment of their thirst.

Ah! Well a-day! What evil looks

Had I from old and young!

Instead of the cross, the albatross

About my neck was hung

is metaphorically illustrating the guilt of killing the albatross: he feels as the albatross hangs around his neck, when, in reality, it had plunged into the water.

Eventually, in an unnatural passage,

the ship encounters a ghostly vessel. On board are Death (a skeleton) and the

'Night-mare Life-in-Death' (a deathly-pale woman), who are

playing dice for the souls of the crew. With a roll of the dice, Death wins the

lives of the crew and Life-in-Death the life of the mariner, a prize she

considers more valuable.

Eventually, in an unnatural passage,

the ship encounters a ghostly vessel. On board are Death (a skeleton) and the

'Night-mare Life-in-Death' (a deathly-pale woman), who are

playing dice for the souls of the crew. With a roll of the dice, Death wins the

lives of the crew and Life-in-Death the life of the mariner, a prize she

considers more valuable.

Her name is a clue as to the mariner's fate; he will endure a fate worse than death as punishment for the killing of the albatross.

Figura - The twaine were casting dice (Gustave Doré, 1876)

One by one all of the crew members die, but the Mariner lives on, seeing for seven days and nights the curse in the eyes of the crew's corpses, whose last expressions remain upon their faces. Eventually, the Mariner's curse is lifted when he sees sea creatures swimming in the water. Despite his cursing them as 'slimy things' earlier in the poem, he suddenly sees their true beauty and blesses them:

a spring of love gushed from my heart,

and I blessed them unaware (284-285)

Suddenly, as he manages to pray, the albatross falls from his neck and his guilt is partially expiated. The bodies of the crew, possessed by good spirits, rise again and steer the ship back home, where it sinks in a whirlpool, leaving only the Mariner behind. As penance for his deed, the Mariner is forced to wander the earth and tell his story, and teach a lesson to those he meets:

He prayeth best, who loveth best

All things both great and small;

For the dear God who loveth us,

He made and loveth all.

Les différentes thématiques de la tradition romantique se retrouvent dans toutes les expressions littéraires et artistiques d'Europe grace à un échange d'idées et d'informations tout au cours su XIXème siècle.

Dans la littérature française il sera possible identifier les mêmes thématiques présentes en Angleterre, en Allemagne ou en Italie:

Le culte du moi: l'écrivain transmet au lecteur l'histoire de sa propre vie, ses souffrances, ses joies. C'est le règne de l'exaltation du "Moi" et le refus du monde extérieur.

L'amour: qu'il soit heureux ou malheureux, il représente une des sources principales de l'inspiration romantique qui exalte la figure de la femme comme médiatrice.

La nature: décrite avec précision, la nature est tantôt la confidente à qui le poète parle, le refuge idéal pour échapper aux contraintes de la société, tantôt la force dévastatrice qui opprime l'homme.

L'évasion: elle s'exprime dans la recherche de nouveaux espaces réels ou imaginaires (goût pour le voyage et le rêve) ou temporels (goût pour la nuit et pour les périodes obscures du Moyen-Age).

Le refus de la raison et le goût du mystère: en opposition avec la raison qui a dominé le siècle des Lumières, les poètes aiment l'obscurité, les visions, l'imagination et les sensations qui sont les clefs pour sonder les profondeurs de l'inconnu et de l'absolu.

Deuz autres thèmes très importants sont ceux de l'insatisfaction de la condition existentielle et de la fuite de la réalité qui méritent d'être approfondies.

Le contraste entre l'individu et les valeurs collectives n'élimine pas l'insatisfaction de l'homme romantique, qui la plupart du temps acquiert un caractère absolu qui lui permet de toucher la matière profonde de la nature humaine et de sa condition existentielle.

En

réalité l'aspiration à l'Absolu, à l'infini, à l'éternité est simplement un

désir irréalisable: en effet, l'homme a pris conscience de sa finitude et de

ses limites infranchissables. Malgré ces limites, l'homme, ne faisant pas

partie intégrante de la nature, a pu entrevoir l'infinité de l'Univers,

l'abysse du temps infini au sein desquels sa propre existence est une pure

casualité.

En

réalité l'aspiration à l'Absolu, à l'infini, à l'éternité est simplement un

désir irréalisable: en effet, l'homme a pris conscience de sa finitude et de

ses limites infranchissables. Malgré ces limites, l'homme, ne faisant pas

partie intégrante de la nature, a pu entrevoir l'infinité de l'Univers,

l'abysse du temps infini au sein desquels sa propre existence est une pure

casualité.

L'insatisfaction romantique en littérature s'exprime aussi dans la fuite de la réalité (et dans les figures de l'étranger et de l'exilé). Une fuite de soi même, de ses propres inquiétudes, se son temps, de la société, a la recherche de paradis exotiques ou artificiels.

Figura - Charles Baudelaire (Nadar)

L'orient par exemple inspira des voyages réels, comme dans le cas du Voyage en orient de Gérard de Nerval, mais stimula surtout des atmosphères mystérieuses comme dans le cas de Baudelaire qui gardera un goût pour l'exotique après un voyage à l'Ile Maurice.

L'activité littéraire de Baudelaire est très intéressante en ce qui regarde les contenus et les influences. Baudelaire est-il romantique, parnassien, symboliste ou encore surréaliste? La réponse n'étant pas simple, on pourrait le considérer tout cela à la fois: romantique pour les sujets imaginaires et obscurs, parnassien pour la soumission aux règles classiques et pour l'adhésion à la formule " l'Art pour l'Art "[3], symboliste pour la présence de symboles qui réfèrent à un monde spirituel et surréaliste pour la supériorité de l'artificiel qui donne un sens profond à ce qui est naturel. Baudelaire représente le point d'aboutissement des tendances classiques et romantiques et il ouvre les portes de la poésie moderne.

Au travers de son ouvre, il a tenté de tisser et de démontrer les liens entre le mal et la beauté, la violence et la volupté (Une martyre). Il a exprimé la mélancolie, l'angoisse de l'homme (spleen)[4] et l'envie d'ailleurs (L'Invitation au voyage). Mais il exprime aussi bien la présence de l'Infini que l'homme ne peut pas atteindre soit à travers l'imagination:

"Il est de certaines sensations délicieuses dont le vague n'exclut pas l'intensité; et il n'est pas de pointe plus acérée que celle de l'Infini

[Petits poèmes en prose ou Le Spleen de Paris (1862)]

Soit à travers les "paradis artificiels" tels quels l'haschich, l'opium, le vin:

"Le goût frénétique de l'homme pour toutes les substances saines ou dangereuses, qui exaltent sa personnalité, témoigne de sa grandeur. Il aspire toujours réchauffer ses espérances et à s'élever vers l'infini

[Du vin et du haschich (1851)]

Même dans ce cas le poète-génie n'obtient pas ce qu'il recherche, mais il a au moins la possibilité de ne "pas sentir l'horrible fardeau du Temps qui brise ses épaules et le penche vers la terre"(Le Spleen de Paris, 1859).

Extrait de la section Spleen et Idéal, le poème Élévation est probablement celui qui mieux exprime l'ascension du poète à un stade idéal supérieur qui coïncide avec l'"air supérieur" et l'Infini:

Elévation

Au-dessus des étangs, au-dessus des vallées,

Des montagnes, des bois, des nuages, des mers,

Par delà le soleil, par delà les éthers,

Par delà les confins des sphères étoilées,

Mon esprit, tu te meus avec agilité,

Et, comme un bon nageur qui se pame dans l'onde,

Tu sillonnes gaiement l'immensité profonde

Avec une indicible et male volupté.

Envole-toi bien loin de ces miasmes morbides;

Va te purifier dans l'air supérieur,

Et bois, comme une pure et divine liqueur,

Le feu clair qui remplit les espaces limpides.

Derrière les ennuis et les vastes chagrins

Qui chargent de leur poids l'existence brumeuse,

Heureux celui qui peut d'une aile vigoureuse

S'élancer vers les champs lumineux et sereins;

Celui dont les pensers[6], comme des alouettes,

Vers les cieux le matin prennent un libre essor,

Qui plane sur la vie, et comprend sans effort

Le langage des fleurs et des choses muettes!

![]()

Dans ce texte, le poète utilise deux moyens pour échapper au spleen. Le voyage réel ne permet pas à l'homme de sortir de son angoisse et de son ennui profonds, au point que la seule libération possible apparaisse la mort. Toutefois, il existe une forme de voyage dont le pouvoir est bien plus grand: celui du rêve et de l'imagination. Baudelaire disait: "l'imagination ne fait qu'un avec l'Infini [.]". L'autre moyen est représenté par la Beauté qui suit de près l'activité du rêve.

Par le rêve, et par l'écriture, le poète est capable d'atteindre u monde idéal et absolu où la seule morale est celle de l'esthétique.

Même en ayant été critiqué par ses contemporains, Baudelaire reste un génie de la littérature moderne française toujours considéré comme le père de la poésie moderne.

Leopardi sottolinea che la tensione verso un'infinità divina, al di là della realtà contingente, non va intesa in senso religioso e metafisico, ma in senso puramente materiale.

|

| Appunti su: https:wwwappuntimaniacomumanisticheletteratura-italianolinfinito-nella-letteratura14php, 6C27696E66696E69746F 696E 6C65747465726174757261, Analogia Zibaldone, tema immaginazione infinito, l27infinito nella letteratura, |

|

| Appunti Grammatica |  |

| Tesine Educazione pedagogia |  |

| Lezioni Pittura disegno |  |